Performance

Life imitating stereotypes, imitating Sense

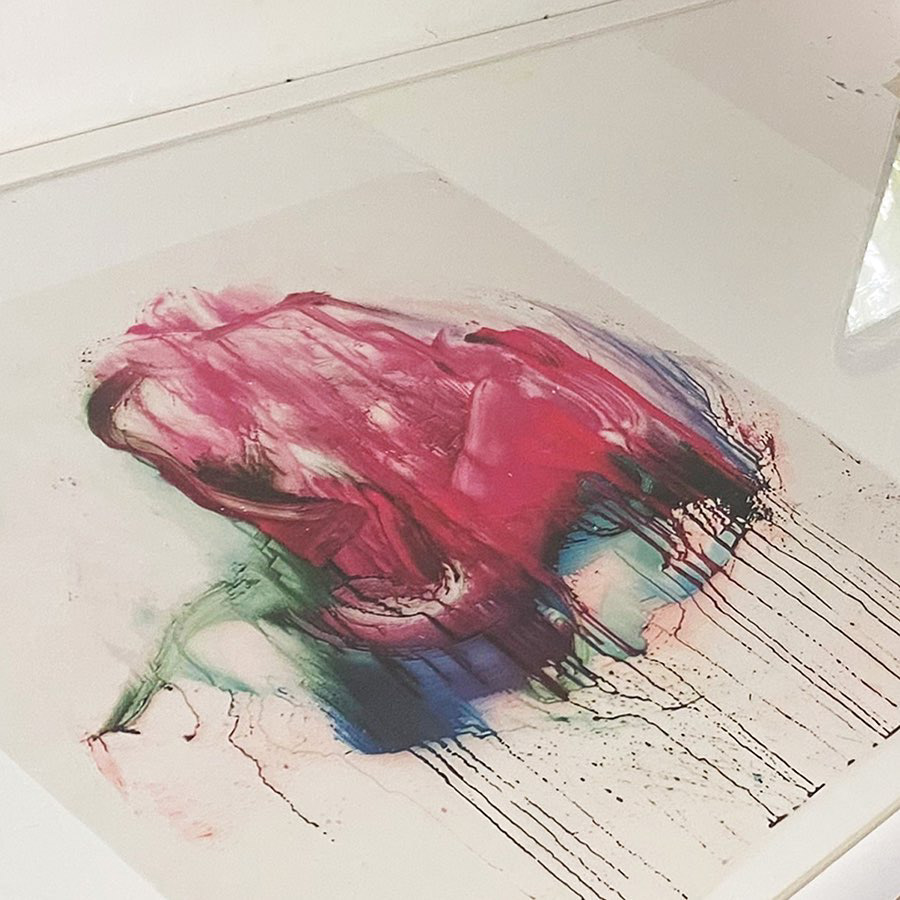

78 inch to 78 inch, acrylic on polyester, 2023

Sensation, Reframed

Giulia Busetti, art historian and curator, 2025

Giulia Busetti, art historian and curator, 2025

Paintings on transparent grounds of various sizes, on the wall and in space, almost forming unstable sculptures come towards us as we enter the threshold of the Cambridge Artworks gallery. On them stand out sometimes anthropomorphic figures, breasts, screams, erupting volcanoes. Threatening magmatic force and traits of informal painting, exploring the possibilities of gesture, materials and sign as the basis of communication. It almost seems as if the emotionality of the film Performance (1) has been transposed onto the grounds from movement-actions to sensations. The fluidity of the colours is still perceptible, as if they could still decide to change. The intense palette from red to bright pink reminds us of the prominent use of the colour red in the film: the colour with which the violent protagonist Chas/James Fox dyes his hair, the sex colour sprayed on the wall, not to mention the countless bloody scenes. "I'm a black and white guy," Chas himself states at one point, as if to convince himself of his disregard for the nuances between the two opposing binaries. 'I feel like a man all the time' he later reaffirms.The images, on the other hand, show through a psychedelia of continuous flickering between the two initially antithetical characters (2) and between their male and female identities, which initially alternate but eventually overlap. This intersection and overlapping of images and sensations creates moments of transition, Venn diagrams perceptible as such only for a few moments, before disappearing without a trace. In reality, the trace remains, only it moves from in front of our eyes to inside our brains: from being an elusive interface image, it imprints itself on the mind in the form of precise sensations like the photograph of a moment that is suddenly there again. Ambivalent and always touching. A similar process occurs in Dagmar Rauwald’s transparent canvases, which activate a similar mechanism in the viewer/spectator when she captures and contextualises the essence of situations in the present.

This transposition from image to sensation situates Rauwald’s work within a broader postmodern landscape. The post-modern condition of the figurative arts from the end of the 20th century to the present day struggles vitally in a labyrinth of references, linguistic models and iconic stimuli, and is characterised by the breaking down of barriers between high and low art, between new and old art, between experimental and traditional techniques. It is a condition of extreme openness and fluidity that is in many ways fascinating, but very problematic insofar as it has challenged previous categories of aesthetic critical definition. In this sense, Dagmar Rauwald's reference to the controversial Sensation exhibition organised by the Royal Academy in 1997 proves fundamental. The exhibition, described by many as "distasteful and disturbing" due to the presence of explicitly sexual images, grotesque genitals, congealed blood, and abstract paintings of overly fleshy female forms, was in fact a major splash in the art world, introducing the YBA (Young British Artist) generation of Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and their contemporaries to a wider audience. One of them, Martin Maloney, recalls how that exhibition essentially mapped the contribution of the participants who 'added to the diversity of what art is and what it can say [...], but above all it engaged and entertained an audience who found in it a reflection of their own pleasures, anxieties and phobias’(3).

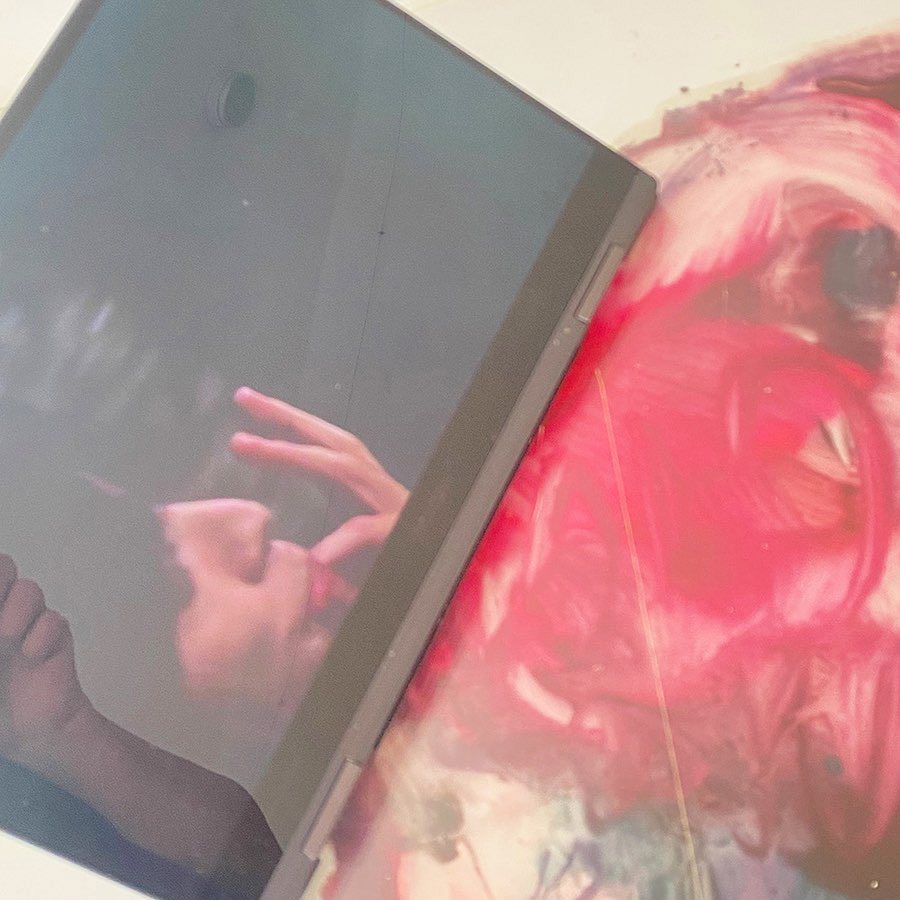

Fast forwarding to 2023 and abandoning the white cube of the Cambridge Artworks gallery, the exhibition takes us inside a van, where the atmosphere becomes decidedly more intimate and cosy, but surrounds us with a sense of intrusion into a private space. The more we enter the space, open drawers and poke around, the more we discover. We make ourselves comfortable on the sofa of what could be the van that belonged to Turner/Mick Jagger, the bohemian protagonist of the aforementioned film Performance, and see an excerpt from the same film running on a laptop monitor, as if someone had started watching it but then left, perhaps annoyed by those very scenes. Violent. Unbearable. 'Sensation' is the ability to physically feel something, especially touching, or a physical sensation derived from this ability: a burning sensation. The Latin root sent and its variant sens mean 'to feel'. Some common English words derived from these two roots are sensation, sensible, resent, but also interestingly enough, consent. Language reminds us that when we perceive something we 'feel' it, and when we are sentimental, our 'feelings' take precedence over everything else. Continuing on this logic, consensus is equivalent to 'feeling' with another, just as dissent instead indicates 'feeling' separated from another. Somehow it seems that these feelings are simultaneously present on and through Dagmar Rauwald's painted canvases, and if the artist herself describes her work as "emotional expressiveness", it is here that we find their full manifestation. Dramatically contemporary, so much so that the very concept of the abstract is almost called into question. Is it what we do not see or what we do not want to see? What are we looking for in the figurativeness of these 'abstract narratives', if emotions, senses, emerge so distinctly and persist in space? Are those emotions, instead, the ugly beasts to be transfigured into the sensational images of the present that constitute our contemporaneity? A further perceptive gap is constituted by the fact that the 1968 film is experienced now (i.e. in the visitor-spectator's present) on a computer screen. The strong initial materiality that initially greeted us through the canvases and their colours seems to have rarefied far beyond a simple change of medium. Movement and colour are indeed transparent but present, as does their support — whether canvas or digital medium. Transparency, then, takes on a temporal meaning. As a provisional situation, it provides us with a space to pay attention to the emissions, cancellations, receptions and recurrences of a multiplicity of inscriptions, semiotics and poetics. Through an aesthetic reading, it seems to offer us a queer aesthetic with a potential for resistance, dissatisfaction and resilience. Perhaps it is even capable of summing up what circulates as sensible matter and what is experienced through friction, slowness, and surprising obliquity in an everyday life that despite the sensationalism of wars, conflicts, and crises of all sorts that follow one another incessantly, both visually and virtually, is delineated as all too linear, tending towards flattening. The chaotic struggle between reading and writing for the absence of errors might emerge in the midst of spreadsheets, in the creation of complex diagrams or in the midst of mumbling discussions useful only to feed the algorithm (4). Activism, however, is not exhausted in the content, but takes place in the process, that is, in the path that that content takes to transform itself from an idea to a reality. From within and beyond specific (infra)structures, Rauwald undertakes impulsive but careful experiments to propose instead trans*feminist infrastructural entanglements, intersectional connection cultures of welcome and hostility in the online structures we inhabit. In doing so, he invites us to other reflections, grammars and actions that contribute to a plurality of interdependent, anti-colonial, trans*feminist, anti-empowering and ecologically just practices of computation, to overcome that performative activism typical of the individual in the digital age, which is reduced to performance instead of consciousness and acceptance of the other. Could thinking in terms of painting, i.e. grasping things in their spontaneity, then become rather a re-thinking in terms of painting, in order to rethink contemporaneity? On the other hand, Turner reminds us, "Nothing is true, everything is permitted."

Proceeding like Dagmar Rauwald, we capture and re-contextualise the essence of those words as a snapshot of that transitional moment in the late 1960s: the foundations of society are fragile, we can't fully perceive the reality, we end up questioning everything, and since our interpretations are shaped by our experiences, the same object ends up being interpreted differently by different people: dissent, consent, and all the senses that run through them, the ambivalence is still there.

Or: Like Rauwald, we re-contextualise Turner’s words as a snapshot of that fragile moment in the late 1960s — when society’s foundations trembled, perception fractured, and meaning became a matter of experience rather than truth.

Notes:

(1) Performance, Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, UK, 1968 (released in 1970)

(2) Representing the opposite poles of late 1960s Swinging London, the gangster and the bohemian

(3) The exhibition quickly caught the attention of TV news, newspapers and tabloids, with the latter expressing new levels of alarmist controversy. The BBC summed up the show as a collection of "gory images of dismembered limbs and explicit pornography”. From The Controversy of the Sensation Art Exhibition, Widewalls, Jan 7th 2020

(4) Science and technology scholar and ecofeminist Donna Haraway calls the “informatics of domination,”Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and SocialistFeminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991), pp.149-181.

(1) Performance, Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, UK, 1968 (released in 1970)

(2) Representing the opposite poles of late 1960s Swinging London, the gangster and the bohemian

(3) The exhibition quickly caught the attention of TV news, newspapers and tabloids, with the latter expressing new levels of alarmist controversy. The BBC summed up the show as a collection of "gory images of dismembered limbs and explicit pornography”. From The Controversy of the Sensation Art Exhibition, Widewalls, Jan 7th 2020

(4) Science and technology scholar and ecofeminist Donna Haraway calls the “informatics of domination,”Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and SocialistFeminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991), pp.149-181.